Guiding Principles for Using Maps in Rangeland Monitoring

This article is adapted from the manuscript Guiding principles for using satellite-derived maps in rangeland monitoring.

The use of satellite-derived maps in rangeland monitoring dates back fifty years. In recent years, advancements have catapulted the discipline into a new era in which consistent map products spanning broad geographies and time periods are increasingly available. However, until now, relatively little emphasis has been placed on training natural resource professionals to properly use and interpret satellite-derived maps, especially when compared to field-based methods. These four guiding principles are intended to help users think critically when using maps in rangeland management.

Principle 1: Use maps within a decision-making framework

Maps supply an abundance of data, providing a spatial and temporal perspective unparalleled by other sources. It is critical to remember, however, that maps are used to inform decisions, but do not actually make decisions. The quantity, availability, and ease-of use of recently produced maps creates an invitation to apply them without thinking through a decision-making framework beforehand.

Before using maps, start with clear objectives centered on the desired management actions or decisions. Then, consider the strengths and limitations of maps relative to the objectives identified. Different tools are better suited to inform different questions, and maps will not be the best tool for every management application and scale.

Principle 2: Use maps to better understand and embrace landscape variability

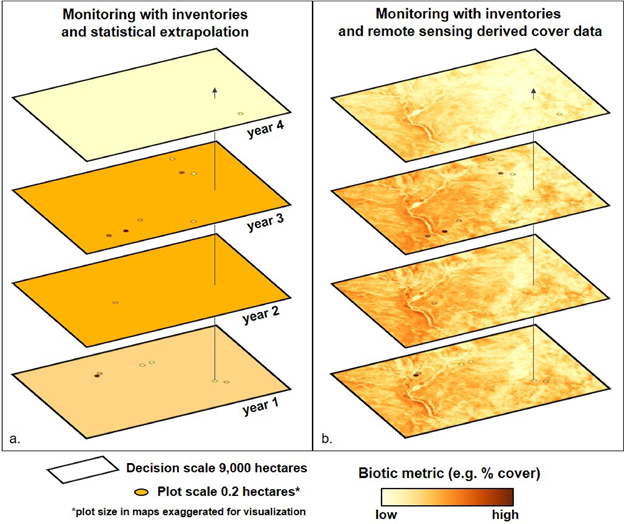

Rangeland management occurs on landscapes. Although obvious, it is important to remember that these landscapes are spatially and temporally heterogeneous; that is, they are variable across space and through time. Given this variability, an important question is, how do we best represent the areas that we manage?

Traditionally, plot-level soils and vegetation data have been collected to inform management. However, in isolation they cannot provide information about landscape variability. Satellite-derived maps, on the other hand, provide a more spatially comprehensive and temporally continuous perspective. When heterogeneity is embraced, maps provide an opportunity to use landscape-wide data to address management questions relating to the distribution and magnitude of heterogeneity across the landscape.

Principle 3: Keep error in perspective

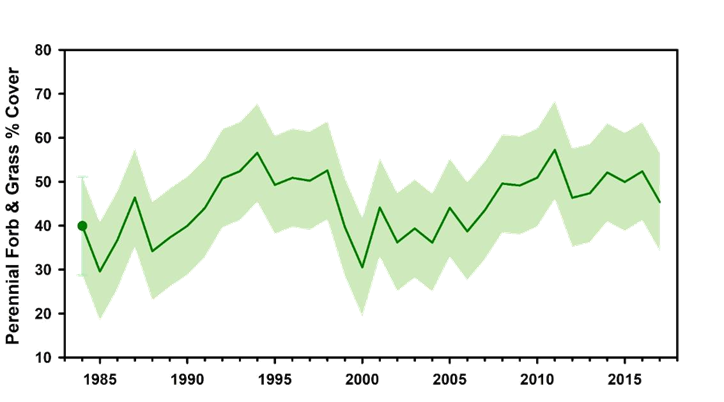

Real or perceived error can be a barrier to the adoption of satellite-derived maps. It is important to remember, however, that error is part of all rangeland measurements, but it isn’t often quantified. The fact that maps have error does not automatically mean they are less accurate or less useful than other data sources.

On a practical level, users must weigh map error and accuracy against the value of the map’s representation of landscape variability. Although map error may appear unacceptably high in some circumstances, it is important to consider error in the context of the decisions that are being made and the alternative information sources available. For many management decisions, low error may not be needed to come to a management conclusion.

Principle 4: Think critically about contradictions

Users of satellite-derived maps are occasionally faced with contradictions from their own world view, other data sources, or other maps. When contradictions occur, it is important to step back and consider the various sources of information relative to the decision being made. Because they may be unfamiliar, maps can be the first criticized, disparaged, or removed from the decision-making process. Due to the abundance of data available in maps, users can zoom in on any pixel in the landscape and determine that the pixel is mapped incorrectly. Doing so, however, ignores the many advantages and efficiencies that maps provide. We not to ‘throw the baby out with the bath water’ but instead to think critically about and understand the contradictions.

When maps contradict other information, including our own perspective, we should question both the maps and the other information. Upon consideration, it may be that they are not as contradicting as originally thought, or that they represent different perspectives. We may learn that the map is not suitable for a specific decision, that another dataset is not appropriate for comparison, or that our own perspective is biased and incomplete. A clear and well defined decision-making framework (Principle 1) will help resolve contradictions when they occur.